Can you squat too much?

The squat has a place in weightlifting and strength training mythos as the king of exercises, save mayyyybe the deadlift. You see it in almost every training program and the typical answer for “how do I get stronger?” from coaches all over the world is to “squat more.”

However, more =/= better. You can certainly squat too much. Placing an overemphasis on squatting will lead to deficiencies in other areas, simply because there is a limit to how much you can train.

Are you using too much of your MRV?

Think of your training like a cup (your recovery ability). Every exercise, set, rep you do adds a little bit of water to the cup (fatigue). Eventually, you’ll reach a point where the water will overflow.

This is your maximal recoverable volume, or MRV. Any training further than will lead to a decline in your performance or even worse, injury.

Therefore, we want to fill the cup as much as we can without any spilling out. Filling the cup halfway with squatting will make you a better squatter, but only leaves half of the cup to work on everything else. If a huge, badass squat is your only goal, then maybe this works for you. For athletes, weightlifters, or people simply trying to get into better shape, this isn’t an economical use of the training load you have.

For example, a weightlifter who spends 50% of their weekly volume squatting, only has the remaining 50% to work on snatches, cleans, jerks, technical derivatives of the classic lifts, pulls, presses and accessories like core work and GPP. That’s less than 8% of your volume dedicated to each of those, which is nowhere near enough to make progress in any of those disciplines.

BUT…

Squatting still has its place. I love squatting, it’s my personal favorite lift and I’d be hard pressed to find an athlete I wouldn’t program squats for, at some point or another. If an athlete needs to work on building absolute strength in the legs, I will bump the volume of squatting up past where I normally would. If a weightlifter finishes a competition and has some time for more of a GPP/volume phase, we will most likely include more squatting than usual as well.

When do we know when an athlete is “strong enough”? We can use tried and true ratios like a double body weight squat, clean/squat ratio, or even an eye test (how well an athlete moves a load).

For example, if an athlete can squat 182 kg (400 lbs), but only cleans 100 kg (220 lbs), the issue is not leg strength, the issue is of a technical origin and we can work backwards from there.

Another tool we can use is the Dynamic Strength Index (DSI).

Dynamic strength index (DSI)

https://www.scienceforsport.com/dynamic-strength-index/

This index is a calculation of an athlete’s ability to produce force quickly in a counter-movement jump (CMJ) compared to the maximal force they can produce in an isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP).

This test measures an athlete’s ability to produce maximal isometric force (the thigh pull), vs. how much of that force can be utilized quickly in a high speed movement (counter-movement jump).

DSI = CMJ peak force (N) / IMTP peak force (N)

Theoretically, the closer the athlete is to a score of 1, the more of their “full force” potential they are able to use during explosive movements (sprinting, jumping, CoD).

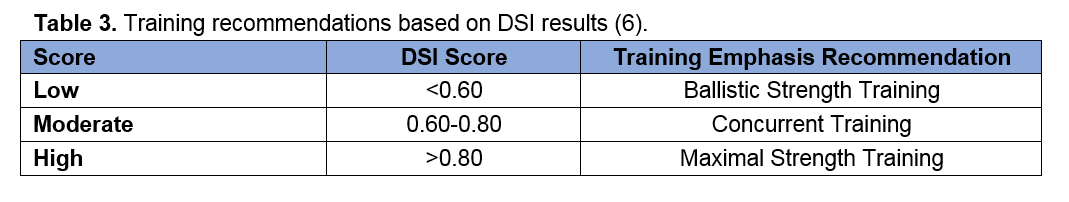

A DSI closer to 1 means more time should be spent on developing maximal strength (i.e. force production). A smaller DSI means more time should be spent developing rate of force production. For athletes with a lower DSI, squatting should most likely not be the primary concern in a training program.

Wrapping it up

Some athletes do genuinely need to squat, and squat more often than they currently are. The same in this entire article could be said for a variety of compound lifts, but it is up to the coach to know when, how much, and with what intensity someone should be doing any given exercise. However, squatting for the sake of squatting is something I commonly see in training programs, especially for competitive weightlifters. Remember, squatting is important, but it’s not a competition lift!

You don’t barbell squat on a football field, and you don’t throw a discus from the bottom of a squat. It’s the most important exercise for leg strength, but it is not the end-all be-all of training your lower body.

Things like DSI are tools us coaches can use to create better training programs for our athletes. If you want a program that looks at every variable and takes the guess work out of your strength work, take a look at our options here.